Is nuclear energy really part of the answer to preventing the devastating effects of climate change? Until the earthquake and subsequent tsunami in Japan, even some ardent environmentalists who’d previously rejected the technology had warmed to the idea.

Nuclear Renaissance?

Recent years have witnessed a renewed interest in nuclear power as people search for ways to prevent the worst of climate change. As part of a so-called nuclear renaissance, some of the myths surrounding nuclear energy have been broadcast with increasing frequency.

Some, including former President Obama, have argued that nuclear energy belongs in the mix as an effective means for combating climate change, and recently the president called for a tripling of public financing for new nuclear power plants.

Obama declared, “If we want to arrest global warming, then nuclear energy is a powerful, powerful ally in that cause.” Obama’s opponent, Senator John McCain, called nuclear energy “one of the cleanest, safest, and most reliable energy sources on Earth.” In the words of the Energy and Environment Awareness Society, a nuclear industry advocacy group, “Nuclear power plants are as clean and as green as wind power.”

Nuclear Proponents’ Misleading Claims

So is nuclear energy really a green answer? It all sounds nice, but it’s profoundly misleading.

For decades proponents of nuclear power have assured the public that nuclear facilities are not only a viable, green means of producing energy but also safe to operate and without risk to human health. To accept this claim requires that we deny the events of Windscale (renamed Sellafield) in the UK, Chernobyl, and Three Mile Island, Vermont’s Yankee reactor, and the National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho in the US, as well as the tragedy presently unfolding at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility in Japan.

Because the Fukushima nuclear power plant’s demise has been making headlines for weeks and has been broadcast on television and computer screens the world over, and because experts warn that it may still be months before the plant is contained and stops spewing radioactive fallout into the environment, Japan’s tragedy is forcing us to take a longer and more thoughtful look at the nuclear energy option.

When Nuclear Goes Wrong

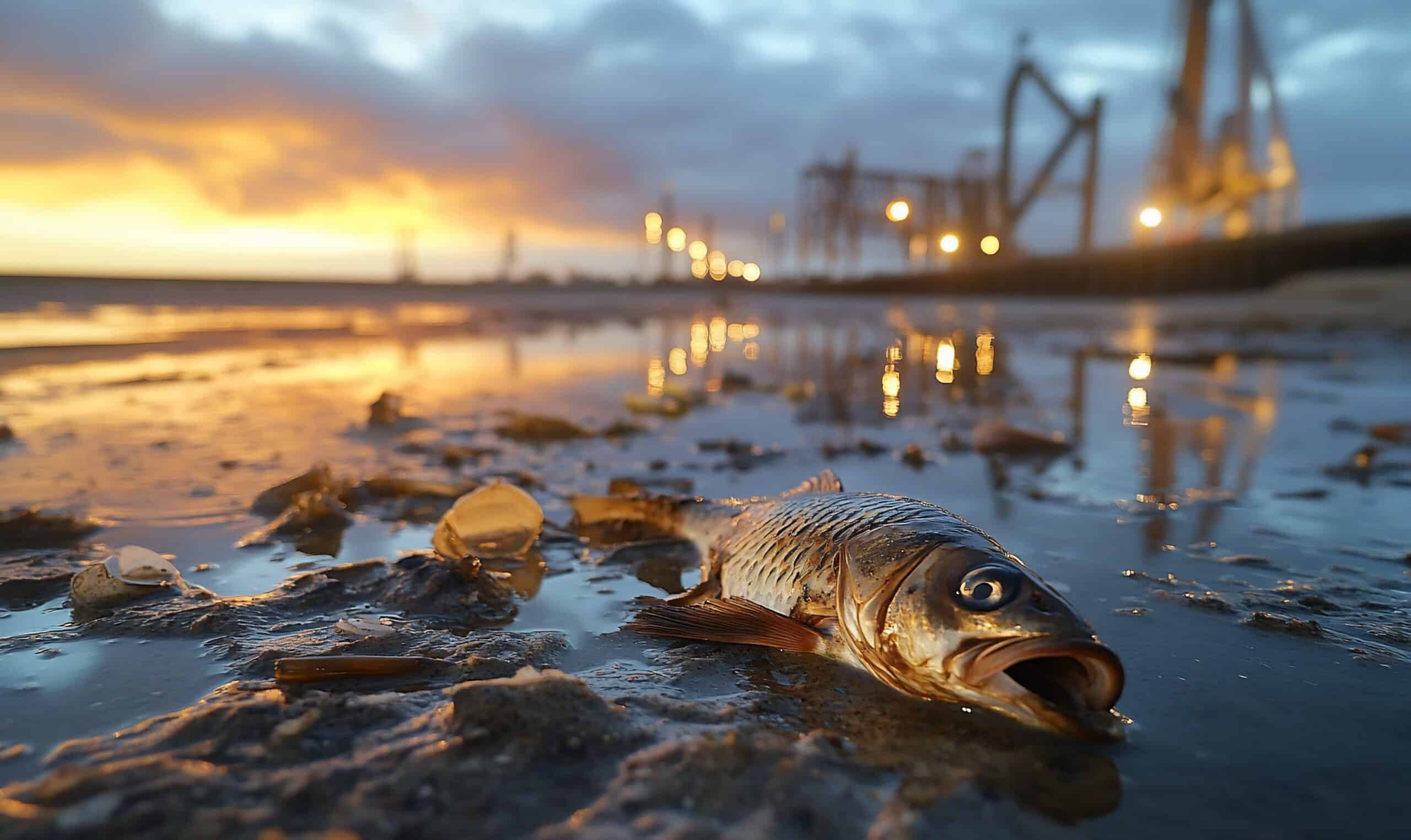

When things go wrong at nuclear power plants anywhere in the world, it’s not just the local citizenry and environment that pay the price. Those who reside thousands of miles away, indeed across oceans, even those not yet born, are potentially affected. The recent detection of Japan’s radioactive fallout in the milk supply in both California and Washington State, and in Boston’s rainwater, is a testament to that fact.

To preempt a panic, officials have done what they’ve always done when there are radioactive releases. They repeatedly state that what’s in the food, air, and water is just a small amount, and that it poses no risk to human health. In truth, no safe dose of ionizing radiation has ever been established. All radiation exposure increases one’s risk of cancer, and each dose is cumulative.

Worldwide there are 443 nuclear power plants operating, 62 under construction, 158 on order, and another 324 proposed. Currently, the US has 104 nuclear power plants, more than any other nation. A meltdown at any of these reactors will distribute radioactive material over at least half the planet.

Nuclear Power and Greenhouse Gases

In its most basic definition, a nuclear power plant is an extremely sophisticated kettle used to boil water. The boiling water produces steam that drives a turbine that runs a generator, which in turn produces electricity.

Proponents of nuclear energy who claim that running a nuclear power plant produces no greenhouse gases neglect to acknowledge the most fundamental part of running an atomic plant: its fuel. And the entire process of acquiring, milling, enriching, and utilizing that fuel, and then managing, reprocessing, storing, or disposing of that fuel — called the nuclear fuel cycle — requires substantial fossil fuel and produces tons of deadly radioactive waste. The nuclear fuel cycle poses a risk to those who work in it, at every step of the cycle.

The fuel, uranium, is toxic and nonrenewable. It requires an enormous expenditure of fossil fuels to mine, mill, and enrich. Mining uranium is hazardous to those who perform the work, and the process leaves behind a staggering environmental hazard. Mining uranium produces mountains of radioactive tailings that must be managed and contained for the foreseeable future.

Today, our nuclear power plants are fueled by only about 5 percent of US-mined uranium, with the balance imported from Australia, Canada, and Russia. So while we’re doing less damage to our own lands and adding less to the tonnage of deadly mining waste at home, we remain the largest nuclear power plant user, and thus the largest importer of uranium. In this way, our demand leads to environmental damage and toxic legacy in the nations that supply us with uranium fuel.

The Byproduct of Radioactive Waste

No discussion of running nuclear power plants would be complete without consideration of its end product — not energy, but more deadly waste. We lack viable means for containing the radioactive waste produced by all of our nuclear power plants. At some point, and at great risk, the waste must be transported through our cities, then contained far from people, earthquake faults, tsunamis, and aquifers, and then guarded. The proposal for the Yucca Mountain storage site in Nevada, located on an earthquake fault, stated that radioactive waste would need to be stored there for 100,000 years — longer than all of recorded human history. Each year, the commercial nuclear power plants in the US alone are producing 3,000 tons more of high-level waste that must be added to the current burden.

Radioactive Legacy

It’s one thing to burden ourselves with the enormously complex, dangerous, and costly process of storing and guarding radioactive waste, but it seems profoundly audacious to presume that we can saddle future generations with such a burden. Imagine the resentment we might hold were we charged with the logistics, risks, and costs associated with storing and guarding deadly radioactive waste produced by the Egyptian pharaohs.

It’s reasonable to assert that we’ve never seen the true costs of building, operating, decommissioning, and storing the waste produced by a nuclear power plant. That’s because we fail to take into account costs associated with storing nuclear waste for hundreds of thousands of years. And what of the costs associated with illness in those who mine, mill, and enrich the uranium that’s used to fuel them? What costs can we assign to parts of the world that are lost forever to increasing tonnages of radioactive mining and milling tailings — toxic for a human eternity? What are the costs to the families who have been exposed from Chernobyl and those who will be sickened and die from exposure to Japan’s radiation? What are the costs associated with those who have for weeks been sent in to face obscene levels of radioactivity in an effort to quell the disaster at the Fukushima plant? Can we place a value on their lives and the emotional toll that will be felt by their families? How about the cost to those in Japan and those near Chernobyl who were forced to evacuate their homes and leave everything behind, and the costs to the governments, and ultimately taxpayers, of resettling those families into new homes possibly hundreds of miles away? Or the cost of the farmlands that can no longer be safely cultivated? Over time, how much of our planet will become uninhabitable due to nuclear waste, nuclear accidents, mining tailings, and groundwater contamination?

The true cost is incalculable.

The Real Path to Containing Greenhouse Emissions

Since the true cost of nuclear energy becomes unacceptable once we look past the myths promulgated by the nuclear industry, how do we contain greenhouse emissions to forestall catastrophe?

True conservation of electricity, and the significant reduction in actual need that would follow, has simply never been employed. A drive around any major city at nighttime will attest to this fact. The skylines are chock-full of high-rise office buildings, uninhabited at night, yet illuminated by thousands of lights. The ever-growing number of personal computers that also remain on in these offices only adds to that energy burden. The same goes for the thousands of car dealerships, supermarkets, and other commercial structures that remain illuminated around the clock. There’s likely not a homeowner in the developed world who couldn’t use less energy. Yet because we do precious little to cultivate an interest in and understanding of effective energy conservation, most of us continue to overconsume, oblivious to the cumulative impact.

Conservation is environmentally, medically, and economically prudent, and it’s a realistic expectation we can hold for ourselves and our society, but someone must lead the way in a bold, demonstrable manner.

Next, we should harness wind power. It has been estimated that the wind capacity of Kansas, North Dakota, and Texas could meet the energy needs of the nation. Then there’s the enormous untapped offshore potential for wind turbines. Add solar, which itself could meet the energy needs of 100 million Americans within 20 years, and one is challenged to justify the risks of nuclear power any longer.

If we were truly inspired to contain greenhouse emissions, instead of building more nuclear power plants we could address the findings reported in the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) study Livestock’s Long Shadow. Published in 2006, the report surprised the scientific community when it revealed that all the cars that choke our freeways, the jetliners in the skies, and the trains traversing our cities don’t contribute as much greenhouse gas as the foods most of us choose to eat. Raising cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens for human consumption produces more greenhouse gases than all the forms of transportation combined.

Vision, Honesty, and Accountability

Skeletal tumors, thyroid and lung cancer, birth defects, radioactive waterways, mass relocations, enormous tracts of forfeited national lands, radioactive food, and enduring deadly radioactive waste — all inevitable if we continue to pursue nuclear power — should not be the price we pay for producing electricity.

When it comes to developing energy policy, we need vision, honesty, and accountability — not only for the sake of those who reside on the planet today but also for future generations who will have to contend with the legacy we leave them.